WHY A LOT OF TOOL STEEL IS BAD

Discover whether antique chisels truly outperform modern tools as we explore the evolution of western tool steel—from bloomeries and blister steel to crucible steel and today’s advanced alloys. Learn why modern chisels often deliver better performance, sharper edges, and greater reliability than vintage favorites.

Updated 2/10/2026

When I started getting serious about woodworking I naturally wanted to invest in better chisels and other edged hand tools. And I was told by almost everyone I spoke to that I should find some old, pre-WWII chisels because old steel was so much better than this modern garbage we have today.

Antique chisels often cost more than modern, high-quality ones.

I admit there is some charm in using vintage tools. And as you can see, I've accumulated a few of them over the years. They are full of history. But are vintage chisels and other tools really better? Or is that just a myth spoken by sentimental people who think all the old ways are better than the dumpster fire of a world we live in today?

Which would you rather own? A 100 year old piece of Sheffield steel or a shiny new modern chisel?

Before you answer, ask yourself, do you really know why Sheffield steel became so prized? It's a fascinating story that goes way, way back and it helps explain why some of today's chisels may not be what you think they are.

The Marvel of Modern Tool Steel

In the picture above is a piece of modern tool steel—a marvel of technology. It has taken centuries of refinement to perfect this material, and we're still improving upon it today. Good tool steel must strike the perfect balance between being hard enough to hold an edge but not so hard that it becomes brittle.

You might think that the harder the steel, the more durable the edge. It’s true that softer steel wears faster than harder steel. However a very hard steel can chip and fracture, especially along the thin cutting edge of the tool. Additionally, harder steel is difficult and time-consuming to sharpen because its resistance to wear from wood also resists your sharpening stone.

On the other hand, soft steel, while easier to sharpen, may dull quickly or even deform, rolling over at the cutting edge. If you've ever tried to chop a mortise in oak with a cheap chisel, you know exactly what I mean.

Finding the right balance between hardness and workability has challenged toolmakers for generations.

The Early Days of Steel Production

Iron itself is relatively soft—too soft for tools like chisels. But by carefully controlling the amount of carbon within iron, it becomes the hard yet workable material we call carbon steel. Achieving the correct carbon levels is tricky, especially in times before modern methods were developed.

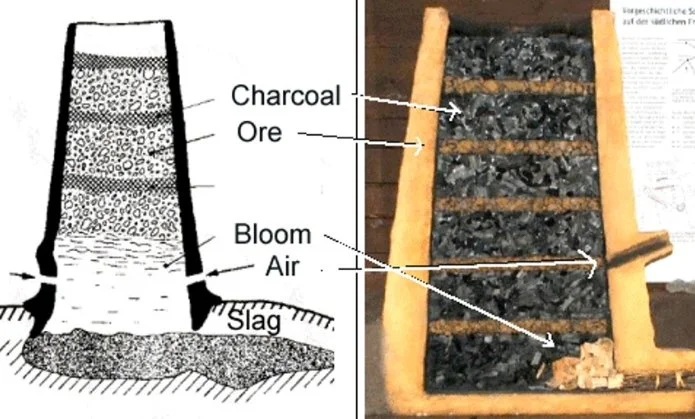

In the early days, iron ore was harvested from the soil and heated in a clay chimney called a bloomery. This process removed the oxides and turned the ore into a usable metal lump known as bloom iron. The bloomery was heated with a charcoal fire, which is pure carbon. The bloom iron produced was so loaded with carbon that it was brittle and unworkable.

Cross section of a bloomery.

To make the iron more workable, it was heated in a forge and hammered over and over, essentially burning out the carbon to create a more malleable metal known as wrought iron, which literally means "worked iron." Wrought iron has a very low carbon content—most of the carbon was burned out, making it too soft for edged tools. While a skilled blacksmith might leave just enough carbon in the iron to create decent steel, it was a very inconsistent and difficult process.

The Rise of Blister Steel and Shear Steel

Eventually, someone figured out that they could put carbon back into the wrought iron by placing it and some charcoal in a sealed box, heating them together for a long time in a hot furnace. The box held the carbon-rich gases from the charcoal, concentrating them around the iron and forming what appeared to be blisters on the iron's surface.

This was known as blister steel. However, most of the carbon content remained on the outside of the iron. To remedy this, the steel was drawn out into thin sheets, cut into pieces, and stacked in layers. These layers were then heated and hammered together to form a solid chunk of steel with carbon distributed throughout. This was called shear steel—a major improvement for tool making, though it was still quite inconsistent due to the uneven carbon distribution.

Shear steel was used for tool making well into the 1800s, but the biggest breakthrough in western tool steel came in the 1700s. A watchmaker, in search of better spring material, developed a process using coke, rather than coal, to achieve the extreme temperatures required to melt blister steel in a sealed container known as a crucible.

The Crucible Process and Cast Steel

By melting the steel in this way, the carbon and iron could be amalgamated consistently. The molten steel was poured into molds to create ingots, which could then be forged and shaped into tools. This method, known as cast steel or crucible steel, became the gold standard for high-quality tool steel. If the process was done correctly, it produced steel with just the right amount of carbon for tool making.

However, the crucible process was time-consuming, making tool steel very expensive. As a result, it was common to forge-weld a thin strip of good steel along the cutting edge of a wrought iron tool (such as a plane iron), as shown in the example below.

It was common to forge-weld a thin strip of good steel along the cutting edge of a wrought iron tool

The Bessemer Process and Industrial Steel

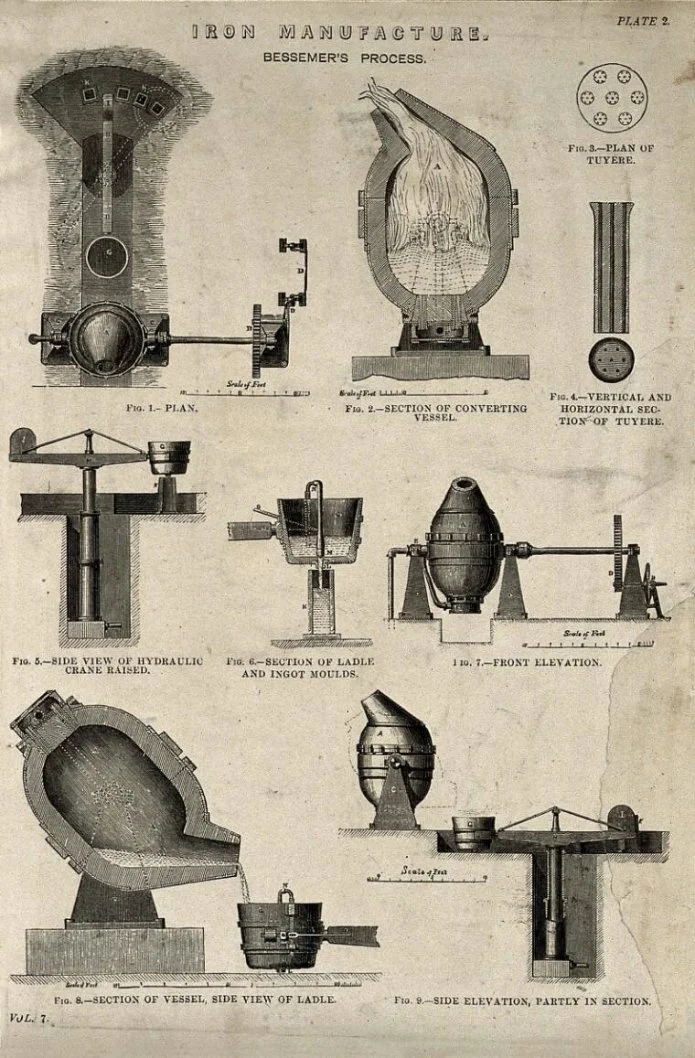

The Bessemer process, developed in the mid-19th century, revolutionized steel production by blasting air into molten metal to remove impurities through oxidation. This allowed for much larger quantities of steel to be produced at a lower cost. However, while the Bessemer process made steel cheaper and more readily available, it was primarily used for industrial purposes like railroad ties, not the high-quality steel needed for tools.

Despite this, smaller manufacturers—especially in Sheffield, England—continued to produce high-quality tool steel using higher quality ores and the older crucible method. To differentiate themselves from mass-produced, low-quality steel, some manufacturers began stamping "cast steel" on their tools, signaling superior quality. The term "cast steel" became synonymous with top-tier tool making, and 19th-century tools from Sheffield, particularly those marked with "cast steel," are highly prized by woodworkers today.

Modern Steel and Its Advantages

Though the quality of tool steel peaked in the 19th century, the evolution of steel didn’t stop there. Both the crucible and Bessemer processes eventually gave way to modern methods, including open-hearth furnaces, which allow for even more consistent carbon levels and improved steel quality.

Today, steel is cast or extruded and rolled into bars, as shown above. A piece of tool steel like this is heated and forged into shape. Unlike in the past, where tools were shaped by repeated hammer strikes, modern manufacturing uses powerful presses to form the steel.

Modern manufacturing uses powerful presses to form the steel.

Excess steel is trimmed and recycled, making the tool blank look more like a chisel. But it’s not ready for use yet. The tool still needs to be hardened because steel that is soft enough to forge into shape is not hard enough to hold the type of edge woodworking requires.

Hardening and Tempering: Ensuring the Right Balance

Hardening involves heating the tool to a specific temperature and holding it there for a set amount of time. This alters the molecular structure of the steel, allowing carbon atoms to settle in and lock into place when the tool is cooled, or “quenched,” typically in oil or water. The result is a dense, hard steel.

A hardened and quenched chisel.

At this point, the steel is too hard and brittle, so it undergoes a process called tempering. The tool is reheated to a lower temperature, allowing some of the atoms to relax. The temperature used during tempering determines the final hardness of the steel, ensuring it’s hard enough to resist edge wear but not so brittle that it breaks.

The stages of modern chisels.

The Modern Chisel: A Cut Above

While hardening and tempering aren’t new processes, modern steel alloys have allowed for further advancements in tool steel. For instance, modern chisels contain elements like chromium and manganese, which enhance impact strength and edge retention. These alloys allow for specialized hardening methods, such as isothermal hardening.

While discussing all the different hardening techniques, new steel alloys, and advanced methods like cryogenics might be a topic for another time, it’s clear that today’s steel is superior to most of the steel used in antique tools. Even a relatively inexpensive chisel today is made with modern alloys and techniques that far surpass the capabilities of old steel.

Conclusion

While it’s true that 19th-century tools from places like Sheffield, England, represent a high point in the history of tool making, modern chisels made with advanced materials and techniques are often far superior. So, if you’re debating whether to invest in antique tools or purchase new ones, it’s worth trying out a modern chisel. I’ll put a link below for you to check one out.

Happy woodworking!

Tools used in this video: Narex Chisels (high quality for an affordable price): https://lddy.no/sqm3

Narex Chisels and other Hand Tools from Taylor Toolworks: https://lddy.no/s80f

Please help support us by using the links above for a quick look around! (If you use one of these affiliate links, we may receive a small commission)