THE HISTORY OF WOOD SCREWS

Explore the history of screws and nails, their strengths and weaknesses, and why nails are still often the best choice for woodworking and construction projects.

For thousands of years, nails were the only metal fasteners used to attach things together. In a previous article, we discussed how nail technology evolved over time—and why old-fashioned cut nails may actually work better than modern wire nails.

Since the original video was released, a lot of folks have asked: why do we still use nails when we can use screws?

That’s an interesting question, and the answer may surprise you. In this article, you will learn the fascinating history of screw technology—and why screws aren’t always the best choice.

Screws as fasteners weren’t used until about the 15th century, largely because it was simply too expensive to produce small screws in any meaningful quantity.

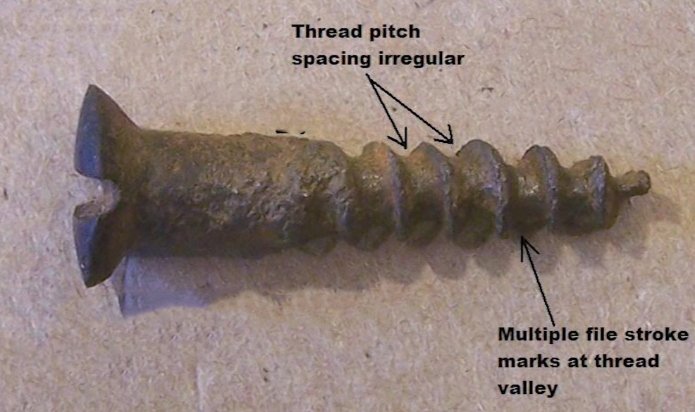

Military necessity seems to have changed that, since some of the earliest examples are found in things like suits of armor and firearms. Like the weapons themselves, the screws were laboriously made by hand, their threads carefully cut with a file. These very early screws can be identified by their irregular threads—each one was unique.

That meant they weren’t interchangeable. If you drove a hand-filed screw into a piece of wood, the threads would cut the opposite pattern inside the hole. If you removed the screw to make a repair and lost it, you couldn’t just use another one, because each screw had its own unique thread pattern. This made screws very valuable—and very expensive.

Furniture Making

But they were also becoming more necessary, particularly in furniture making, as metal hardware became more common. Securely attaching something like a drawer pull with nails might require a process called “clenching,” where the nail is driven all the way through the drawer front and bent over on the inside like a staple. That may be cosmetically acceptable if you never look inside the drawer—but what about other hardware, like locks, that must be attached from the inside? You don’t want nail ends showing on the outside of the drawer.

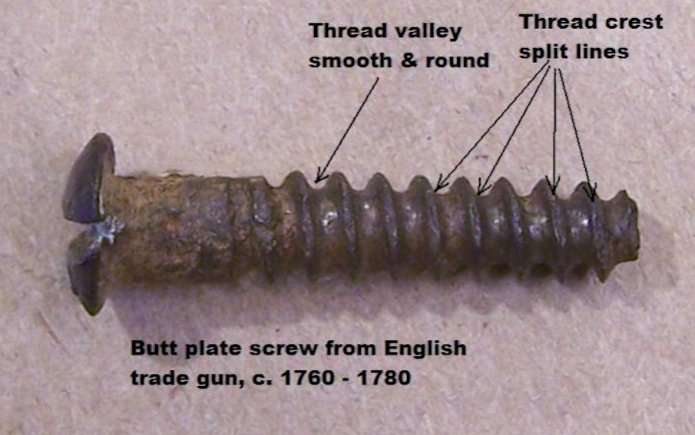

Screws solved these and other furniture-making problems—especially after the development of lathes in the 1760s, which could make screws with evenly spaced and consistently shaped threads. It was still a relatively slow and costly process, but for the first time, screws became consistent in size and interchangeable.

These early lathe-turned screws can sometimes be identified by the off-center and irregular slots on their heads, which were often still cut by hand with a chisel or saw—sometimes even by the woodworker himself after receiving them in his shop.

At that time, virtually all screws featured straight, untapered shafts and blunt ends. The end user was required to bore a large pilot hole before driving the screw inside.

It wasn’t until the late 1840s that new screw-making machines began producing screws with both tapered shafts and pointed ends. And it may have been as late as 1856 before consistently centered, machine-cut slots became common.

These and other changes to screw technology over the years can help experts determine the age of certain pieces of furniture—sometimes even narrowing it down to within a few years.

Fed up

After the Civil War, screw technology changed little—until folks finally got fed up with the slotted head design. Anyone who has used them knows how easily the driver can slip or “cam out” of the slot and damage the workpiece itself.

In the late 1800s, many alternative ideas were tried, but none caught on until a Canadian named Robertson perfected a square recess. What became known as the Robertson drive was a great improvement that immediately began to take off—until Henry Ford failed to secure the terms he wanted for using them in his U.S. auto factory, and instead backed a star-shaped drive that became known as Phillips. Phillips head screws took off during WWII and became the standard in America, while Canada continued to favor Robertson heads.

Phillips screws do strip and cam out much easier than Robertson heads, but industrial machinery took advantage of that flaw because it allowed the driver to pop out of the screwhead once the screw was fully seated. Still, the search for a better drive continued, and today there are many different styles available. I personally like Torx head screws—even if they are ugly as butt.

As mechanical fasteners, screws have become as common as nails. But the screw has never replaced the nail, and in some applications, the nail is still the superior fastener. The difference is in how they function.

Comparisons

Screws can’t be beat for resisting tensile forces that try to pull two pieces directly away from each other. But they are generally weak against shearing forces that try to slide two pieces apart.

If you’re hanging something from a ceiling, a screw is less likely to draw out over time. But if you’re attaching something to a wall, a screw is more likely to shear off under excessive weight.

That’s because screws are made from much harder—and more brittle—steel than nails. You can break many screws fairly easily by bending them. A nail, on the other hand, will bend many times before breaking.

This is a critical difference—especially in construction. Houses are typically framed with nails not only because they’re less expensive than screws, but also because houses move and settle over time. Nails can bend as needed, while screws may not.

That said, some modern construction screws are specifically designed for structural uses. But their high cost makes them impractical for general framing.

Nails are also valuable in furniture making. For example, you can’t glue a moulding across the grain of a solid wood panel. Changes in humidity will cause that panel to swell and shrink over time—and either the glue bond will fail, or the panel itself will split. But a few small nails will hold the moulding in place without restricting the wood’s natural movement. And unlike screws, nail heads may be small enough to hide.

Some of the finest pieces of antique furniture—stuff that’s lasted for generations—feature nails for attaching mouldings and other critical parts, including cabinet backs and drawer bottoms.

That doesn’t mean you can fill a project with nails. Too many can still overly restrict the wood. But a few small nails in the right places can create a unique, flexible joint that will stand the test of time.

Nowhere is this principle better illustrated than in the traditional six-board chest, which is typically built with horizontal wood grain on the front and back panels, but vertical grain on the side panels.

A traditional six-board chest.

Normally, crossing grain directions like this can lead to disaster—because boards may swell or shrink in width, but never in length. The side panels should restrict the movement of the front and back panels, and in time, they should split apart.

But if these panels are connected with some strategically placed nails, they can move just enough due to the flexible nature of the nail itself.

Both nails and screws may seem like relatively simple fasteners. But they’re equally rich in history and technology—and both maintain their rightful places in our modern toolkits.

Need some cool tools for your shop? Browse my Amazon Shop for inspiration.

(This link is an affiliate link. If you make a purchase, I may receive a small commission.)