IS JAPAN SLOWLY KILLING WESTERN-STYLE SAWS?

Japanese saws cut on the pull stroke, keeping the blade in tension for thinner kerfs, greater accuracy, and less effort than traditional Western saws. This guide explains how they work, their real pros and cons, and how to choose between Ryoba, Kataba, and Dozuki saws for your woodworking needs.

I’ve often thought it was curious that Eastern woodworking tools—such as planes and saws—are often designed to cut in the opposite direction as those developed in the West.

Take, for example, the traditional Western-style handsaw. It cuts when you push the teeth away from you through the wood. A traditional Japanese saw, however, cuts when you pull the teeth toward you.

The same is true with hand planes: Western planes are pushed, while Eastern planes are pulled.

This is especially interesting when you remember that the two hemispheres developed largely independently of each other. Cutting on the push stroke wasn’t developed as an improvement over the pull stroke—most early Western toolmakers had no idea things were done differently on the other side of the world.

Fortunately, today many of us have access to both types of tools and the ability to compare them. I’ve been a big fan of Japanese saws for a long time—and so have many other woodworkers on this side of the globe.

But there’s still a great deal of confusion about how these saws work, the differences between the types available, and whether a Japanese saw is right for you. Most videos and articles focus on the benefits of these tools while largely ignoring the downsides.

In this article, I want to present a clear, concise guide to the pros and cons of the three most common types of Japanese saws, so you can make an informed decision about which to try—if any at all.

Why Choose a Japanese Saw?

When you push a saw through the wood, the force is coming from behind the cut, and the blade can bend under pressure. If you hit a significant catch, you can damage the saw—or, more often, you’ll simply find the blade harder to steer. Think of it like a rear-wheel-drive car on a snowy road: when the power comes from behind, the front end is more likely to drift.

A front-wheel-drive car, by contrast, is easier to control because the power leads from the front—and everything else follows. That’s why many people find it easier to follow a precise line with a Japanese pull saw: the handle leads the cut rather than pushing it forward.

Pulling the saw also keeps the blade under tension during each stroke. This allows for a thinner blade, which cuts a finer kerf faster, with less effort, and produces less sawdust. You’ll notice the difference in speed and effort right away.

A thinner kerf also means better guidance.

Western saws require a wider kerf than the blade to avoid binding—because the force is compressing the blade rather than stretching it. This wider kerf is created by a greater “set” in the teeth (how much each tooth is bent outward). The result is more room within the kerf for the blade to move side to side—potentially wandering as you cut deeper into the wood.

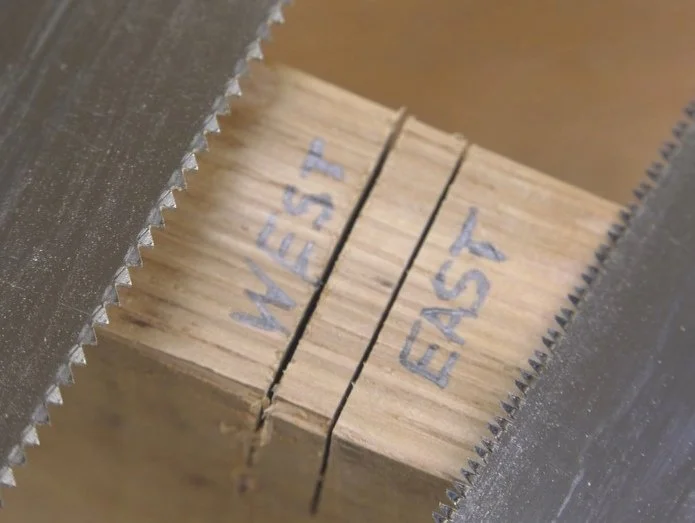

Western vs Eastern saw kerfs.

Japanese saws, in contrast, are under tension during the cutting stroke, so they’re less likely to bend or bind. The teeth can have a much slighter set, which means a narrower kerf that better fits the blade. Once you begin a cut, the kerf helps guide the saw as it goes deeper into the wood—reducing the chance of drifting off-line. That’s another reason many people find Japanese saws more accurate.

Durability and Cost

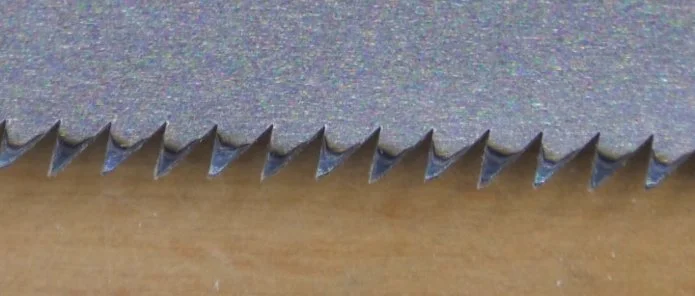

Teeth of Japanese saws.

Many Japanese saws also stay sharp longer because their teeth are impulse-hardened. When they do dull, you simply remove the blade from the handle and snap on a new one. That might sound expensive, but consider this: you’d need to sharpen a Western saw multiple times to match the number of cuts a hardened Japanese saw can make before needing replacement. When you factor in the time and cost of sharpening, replacing a Japanese saw blade every few years for $15–$20 makes a lot of sense.

And surprisingly, Japanese saws are quite affordable—especially when compared to high-quality Western saws. The ones I use are made in Japan and cost around $30–$40 from a small Missouri company I’ll link below. Compare that to a well-made, properly sharpened Western saw capable of equally precise cuts.

Precision and Feel

Precision might be the biggest advantage of a Japanese saw. Besides being easier to guide and producing a finer kerf, they also provide better feedback—a subtle feel for the cut. It’s hard to describe; you have to experience it to understand. The pull stroke simply changes the way you cut. It’s more comfortable across a range of positions, even two-handed. It’s less fatiguing, and it often gives you a better view of your line.

The Downsides

That said, Japanese saws do have a few cons.

While the pull-cut motion keeps the blade straight during the cutting stroke, improper technique can still cause binding on the return stroke. The thin blade can kink if you don’t move it straight.

Also, the hardened teeth—while long-lasting—are more brittle. It’s easier to break a tooth on a Japanese saw than on a softer Western one, especially if you catch a tooth on the return stroke in very hard wood.

Both issues can be greatly reduced with proper technique: keep your strokes smooth and deliberate, and only increase speed as you get more comfortable with the feel of a pull-style saw.

If you prefer to sharpen your own saws, hardened Japanese saws might not be for you. You can buy high-end versions with sharpenable teeth, but sharpening them—especially crosscut teeth—requires special tools and skills. There are also very few sharpening services for Japanese saws in the U.S., so you may have to send them to Japan.

Another potential downside is the straight handle, which some people find less comfortable than the pistol grip of Western saws. Switching can take some getting used to.

The Three Main Types of Japanese Saws

Let’s break down the three most common types of Japanese saws:

Ryoba

The Ryoba is a general-purpose saw for both hard and soft woods. It's easily identified by its two sets of teeth—one for ripping with the grain, and one for crosscuts.

The Ryoba I use has a 250mm blade, which is great for general carpentry and rough-sizing parts. They come in different sizes, but 250mm is ideal for most people.

Think of the Ryoba like a Western panel saw—except it does both rip and crosscuts, whereas a Western woodworker would need two different saws for those jobs. The downside? The non-cutting edge can sometimes mar your work, especially on long cuts. But for rough work, this isn’t a major concern.

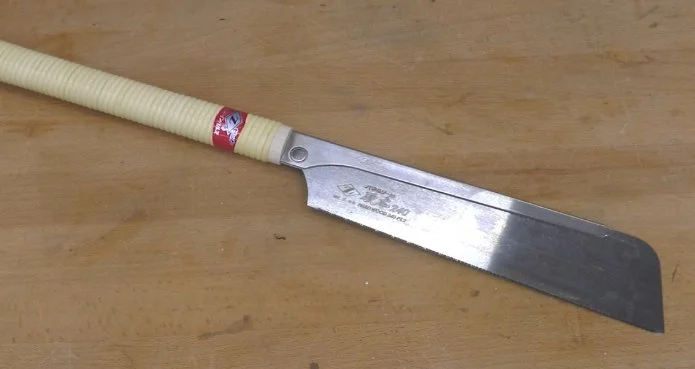

Kataba

“Kataba” means “single edge.” It has teeth on one side only, which can be filed in different ways for different cuts—typically either crosscut, rip, or universal (which looks like crosscut to me).

The Kataba is more of a precision tool. It’s ideal for furniture parts, joinery cuts, and flush cutting, thanks to its flexible blade. It’s comparable to a Western carcass saw. I use one around 265mm in length with universal teeth, which covers most of my needs.

Dozuki

The Dozuki is my favorite. “Dozuki” roughly translates to “shoulder cut,” and this saw is meant for fine joinery—like dovetails.

Dozuki saws have the thinnest blades of all, so they require a reinforcing spine. This makes them ideal for very precise work.

The ones I use come with 21 TPI for hardwoods or 25 TPI for softwoods. Finer teeth give you more control in softwoods, while coarser teeth help efficiency in harder woods.

Most Dozukis on the American market are crosscut-filed because you’re usually only doing short rip cuts—no deeper than the distance from the edge to the spine—so dedicated rip teeth aren’t as necessary.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

Honestly, I enjoy all three types of Japanese saws. And they’re affordable enough that most woodworkers can own more than one.

Here are my recommendations:

Dozuki: Start with a medium size (around 240mm) and 21 TPI—ideal for hardwood between ½″ and 1″ thick, and also usable in softwood.

Kataba: Look for a 265mm version with universal or crosscut teeth. Perfect for clean crosscuts, larger joinery, and flush trimming.

Ryoba: Go for a 250mm model. Great for fast sizing cuts when a power tool isn’t worth the mess.

I buy mine from a small family-run business in Missouri called Taylor Tools. They offer excellent quality at great prices—and they’ve supported the Stumpy Nubs channel for a long time. If you order through my link below, it helps support us too.

Tools used in this video:

-Ryoba (fast, rough cuts): https://lddy.no/1m1f9

-Kataba (finish cuts, flush cuts): https://lddy.no/1447e

-Dozuki (ultra-fine cuts and joinery): https://lddy.no/1cd7y

Need some cool tools for your shop? Browse my Amazon Shop for inspiration.

(These are affiliate links. If you make a purchase, I may receive a small commission.)